Covers (to 1933)

Seeing as by this point I've got most of the lower-value stamps I'm looking for, and kicking my heels in hopeful anticipation of the high values appearing for a decent price isn't especially productive, I've decided to try to branch out into covers, which is an area I'd previously rather neglected. My stock of these at time of writing is very slight, so my intention is to populate this page with new acquisitions as I acquire them. Anyway this page will go down to the death of Faisal I, and the second page will cover everything after that.

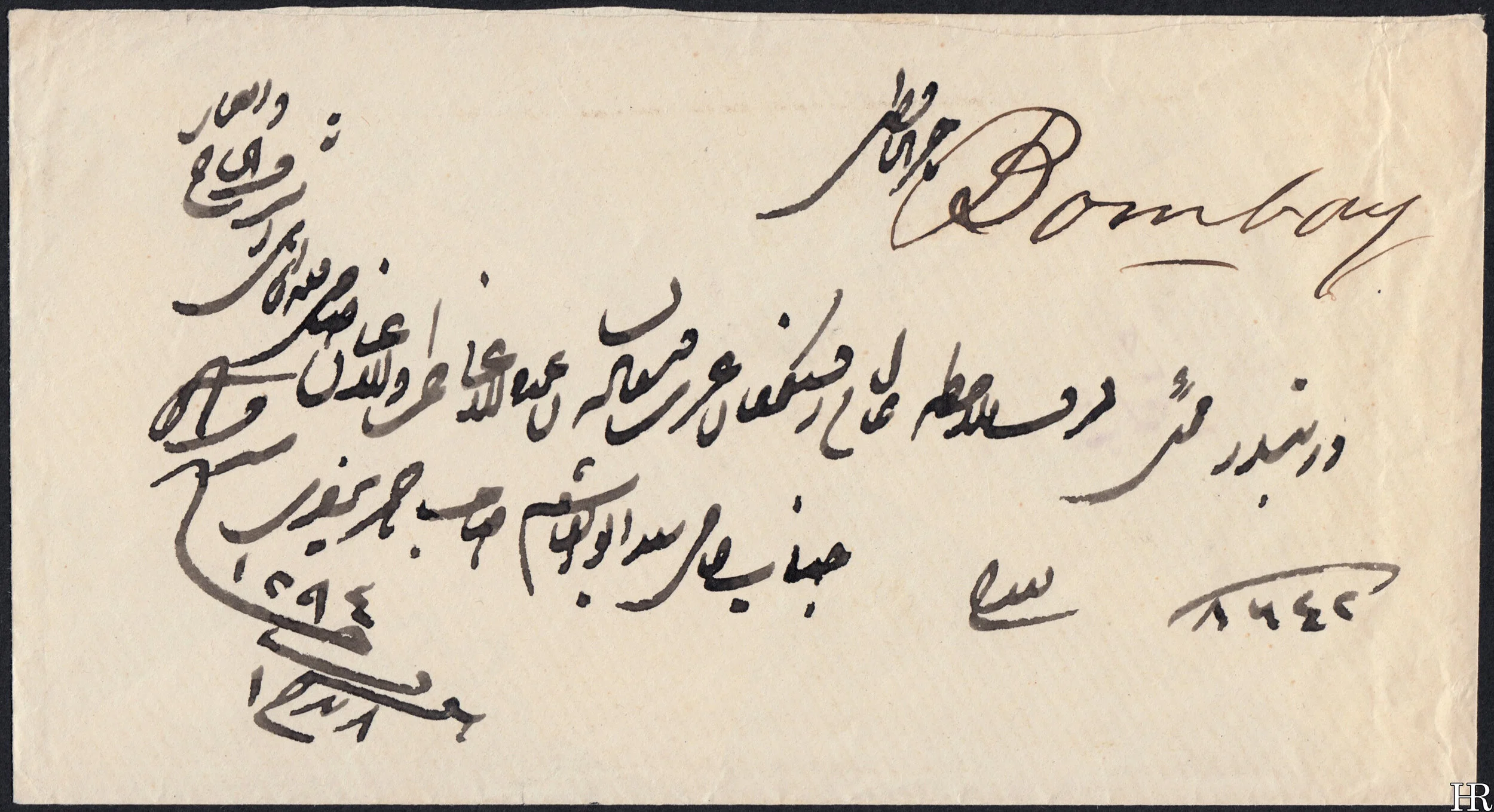

Basra 🠚 Bombay, 22 May 1876/7

Handsome product of the British post office in Basra. Postmarked 22 May and arrived at Bombay on 8 June. The year is more challenging: it’s entirely unreadable on the Basra postmark and the lovely clear Bombay one doesn’t deign to provide it. Proud gives the Basra mark (his “D2”) earliest and latest dates of 1870 and 1874, based on covers seen by him. I think I can make out a manuscript Islamic date ١٢٩٤ on the bottom-left of the cover, which coverts to 1876/7 by the Gregorian reckoning. This is a little outside Proud’s date range but, I think, not implausibly so.

As a digression, the Anglicisation of “Basra” was charmingly unfixed at this early stage: 19th-Century British postmarks can be found reading “Busreh” (as here), “Busrah”, “Bussora” and the very emphatic “Bussorah”.

Mosul 🠚 Diyarbakir, 3 May 1880

Covers of the Ottoman post are something of an “investment” for me, in that I someday hope to be wise enough to understand them much more than I currently do. I am of course entirely ignorant of the scripts and the underlying languages, but the rates and postmarks are at time of writing almost equally mysterious. So unfortunately my analysis of these items will be superficial and dependent on such notes as arrived with them.This was written up by its previous owner as posted at Mosul, with a manuscript date of 3 May 1880 (converted from its Islamic equivalent presumably) and addressed to Diyarbakir. I take all this at face value.

The postmarks are of the early “triple box” variety and bear the date ٨١, Gregorian 1865. This can’t be the actual date of postmarking, because the stamps used here (of the charming “Duloz” design) weren’t issued until 1870 or 1871. Was the year deliberately immobilised, perhaps reflecting the year the postmarks were sent to the post offices? I have an off-cover Duloz postmarked at Baghdad where, again, the postmark is dated 1281 and pre-dates the stamp underneath it. No doubt the answer to this conundrum is known, but I do not know it. Total franking is 60 paras or 1½ piastres, which apparently was the standard rate for an internal letter.

Baghdad 🠚 [Somewhere], 7 November c. 1885

No doubt an educated man could read the destination in a second, but I am not an educated man. I see no manuscript date on the cover, and the date on the postmark is mostly illegible. I think I can make out “188-”, and the underlying stamp was issued in the earlier 1880s, so I’ve gone with circa 1885 up top, which hopefully isn’t completely off-base. I suspect the destination is foreign, considering that the stamp is of the “UPU” issue and the postmark of the French “BAGDAD / TURQUIE” variety. Franking is 1 piastre, which seems to have been the applicable rate for both foreign and internal mail around this time.

Kerbela 🠚 Tehran, 1898/9

Large purple Kerbela (or Karbala, if you prefer) postmark cancelling a pair of the unattractive 1892-1898 issue. I can’t read a date on it, but there seems to be a manuscript ١٣١٧ on the reverse: this works out as 1898-1899 and thus accords neatly with the date of the stamps. Smudgy “TEHERAN” postmark on the reverse, in the distinctively seriffy Iranian style.

Baghdad 🠚 Edinburgh, c. May 1900

Pleasant, fairly self-explanatory item. Main point of interest is that the sender, presumably a Briton, has patronised the Ottoman post office instead of the British one — more touristic value in the former course, perhaps. I can only assume the franking is more or less what it ought to be. The postmark date is illegible to me but, I assume, for it to have arrived on the 14th June it must've been posted in late May. Franking is 40 paras or 1 piastre. Note the “via Beyrout” at top-left. Misses Cowan seem to have operated a small boarding school or something of that nature, from a brief search.

Baghdad 🠚 Mosul, 9 December 1901

A few agreeable aspects here. A nice example of up-rated postal stationery: here a total of 40 paras (1 piastre). Cancellations are of the charming BAGDAD-in-oval type, and we have a clear dated bilingual postmark that gets a little tortuous once you peer into the date line. I think I can discern “9-12-901” on the Gregorian side, and the stamps (the 1901 issue) don’t contradict this date, but I could well be wrong. The sender is some official of the Baghdad branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, writing to his colleague David Yusuf at the rather militaristic-sounding “Bible Depot, Mosul”. A 1910 History of the British and Foreign Bible Society (available online) describes modest successes, and considerable hazards, in evangelising to the locals. An encounter with hostile Arabs left one party of missionaries "robbed of all they had, barbarously ill-used, and left, hungry and naked, to find their way after a day and two nights into Mohammerah." Another missionary was "beaten by a sheikh and left tied to a tree."

Kerbela 🠚 Tehran, 2 November 1910

Another difficult postmark. This one seems to read “2-11-910”, but that doesn’t fit at all neatly with the Iranian arrival postmark which appears to be dated 3 September 1911. I suppose the thing could’ve taken ten months to reach its destination, but that hardly seems likely. The previous owner dated the Ottoman postmarks as 19 July 1911 but, respectfully, I don’t think I can agree with that reading. This mystery aside, we have two blocks of 4x5 paras for the usual total of 40 paras or 1 piastre.

Kadhimiya 🠚 Isfahan, 1913

Handsomely calligraphed and handsomely postmarked cover from Khadimiya (a northern suburb of Baghdad) via Kermanshah to Isfahan. The markings, again, are less straightforward than they might be. Here we have:

Kazimié

Baghdad No. 4, 10 September 1913

Kirmanchah arrivée, 2 October 1913

Isfahan No. 5, 13 October 1913

The Khadimiya postmark (in violet, uncommonly) appears to read “14-3-13”. A March date doesn’t fit in at all with the three later ones, so at this point I throw my hands up. The tughra handstamp on the reverse is curious: does it suggest this was sent on some kind of official business or other? I do not know.

Baghdad 🠚 Frankfurt, 27 May 1914

Generously uprated registered envelope. Here we have an extra 70 paras’ worth of stamps, giving a total franking of 2¾ piastres. What particular rate this met I cannot advise. The stamps are postmarked 27 May 1914 and on the reverse is a Frankfurt (am Main) arrival mark dated 11 June 1914. The handstamp on the obverse I assume is connected with the registration. Recipient is one Ferdinand Blecher(?) and the sender is evidently a relative.

Basra 🠚 Baghdad 🠚 Bombay 🠚 Kirkee, 3 February 1919

Well-travelled cover sent by Lawrence & Mayo, opticians, to one Lieutenant J. E. Ogle, who turned out, after some diversions, to be resident in Kirkee (now Khadki, India, and seemingly still a place with strong military connections). On the obverse we have a single 3 anna stamp paying the 1 anna internal rate plus the 2 annas registration rate, and on the reverse a nice jumble of postmarks. These, as far as I can make them out, are:

Basra, 3 February (obverse);

Baghdad, 6 February;

Field Post Office 55 (stationary FPO, Baghdad), 7 February;

Field Post Office 55 (stationary FPO, Baghdad), 9 February;

Baghdad Base Post Office, 10 February;

Field Post Office 367 ("in Iraq"*), 14 February;

Bombay? [not easily read], 3 March;

[Illegible], 5 March.

The final item is probably the Kirkee arrival mark: the internet has it only a couple hours' driving away from Bombay. Most of the amendments to the address are self-explanatory, but I've got nothing on the small manuscript numbers (something to do with the registration?) and the word written in red at the top.

Of interest, the 21 November 1916 issue of the Basrah Times (at time of writing on sale at the Balkanphila website) contains this advertisement:

LAWRENCE & MAYO

OPTICIANS,

Have opened a workshop at 16

CHURCH STREET, ASHAR

—near the barracks—

————

Glare Protectors, Spectacles & Eyeglasses, etc.

————

Prescriptions & Repairs Executed.

*Per Proud: vagueness as in original.

Mosul 🠚 London, 4 June 1919

The Mosul issue is scarcely found on covers, especially ones which, like this one, appear uncontrived. This cover seems actually to have been under-paid: since 1 September 1918 the basic foreign rate had been 1½ annas. The recipient, one H. L. Ashford Esq., seems not to have been anyone in particular. No markings at all on the reverse, which isn’t surprising for an un-registered cover, but some hint that this had actually passed through the mails would have been reassuring.

Basra 🠚 Baghdad, 19 October 1920

Dear George, How are you all? And why do you not write to me. In spite of 'Arab' troubles we are still alive & in good form. Love to all, Yours Ever, Arthur J. Treasure. Magil, Basra, 28/10/20

This is definitely something, though beyond that I've got rather little idea. We have, on the obverse, a 1½ anna postmarked with what appears to be a registration-label handstamp. On the reverse, the following postmarks: a Basra sub-office (Dorset Bridge? a terminal 'e' is just about visible), 19 October; Lower Baghdad, 21 October; and what seems like another Dorset Bridge, almost entirely off the cover. On the reverse, additionally, is an entire message, dated 28 October at Magil, Basra. The recipient is a Major Arthur Treasure, offer in charge of the Navy and Army Canteen Board office in Baghdad.

What seems to have happened here is that Major Treasure, having received the envelope at Baghdad, took it with him to Magil, where he composed the message on the reverse. There's nothing to suggest that this second message passed through the mails, so I would assume he simply handed the letter to someone (a mobile army colleague, perhaps) capable of passing it onto "George."

The strangeness of the postmark on the obverse I cannot explain. My guess is that the regular Basra canceller must've been incapacitated, for whatever reason, and somebody decided to use the registration handstamp to replace it. This would explain the (otherwise unusual) Dorset Bridge postmarks: the cover was posted at Basra (the main office, I must assume?) and arrived (for whatever reason) at the Dorset Bridge office, whereupon someone noticed the irregular postmark and applied a "regular" one before it went out to Baghdad.

According to Proud, the inland rate for a basic-weight letter at this time was 1 anna, increasing in increments of 1 anna. This is franked as 1½ annas, as is the cover below. Are they both overpaid, or was there a rates increase missed by Proud?

The context here, of course, is the anti-British rebellion which had just been suppressed: the "Arab troubles" referred to in the message. Although the worst of it was over by mid-September, and it seems never to have troubled Baghdad too greatly, Proud offers some colourful descriptions of several alarums experienced by its inhabitants. The revolt doesn't seem to have come anywhere near to Basra, so Major Treasure must be referring to his experiences at Baghdad, or wherever else.

Mosul 🠚 Baghdad, 28 May 1921

Service stamps on cover aren't commonly encountered:* I try to pick them up on the few occasions I can actually find them up for sale, even if they're not necessarily extremely interesting. This item here is rather straightforward: an internal letter from Mosul to Baghdad, posted on the 28 May and arriving on the 2 June. Note that the stamps used are the regular occupation issue, despite this having been posted within the currency of the special Mosul issue: this prompts the question, which I hadn't ever considered prior to writing this very sentence, of what persons entitled to send official mail did in Mosul in this period — the Mosul issue was of course never overprinted for service use, so was the service version of the occupation issue just used without interruption? Answers on a postcard. The franking here I must assume is correct: see my remarks on rates below the above cover. I'm also unsure about the formalities required to send official mail at this early period: the familiar "official must sign at the bottom-left" procedure was possibly only introduced in 1925. The "No. 2292" at top-left is probably something, but what I do not know.

*They certainly feel disproportionately scarce compared to the relative availability of off-cover used service stamps. Couldn’t begin to guess why.

Baghdad 🠚 Hebden Bridge, 27 November 1927

Pleasant item despite a few disfigurements. The obverse is rather busy: we have the requisite official's signature and title at the bottom-left corner, but also an additional inscription at the top-left on which I cannot advise. I can read “cheque”, so presumably it’s a docket of some sort. The "on state service" handstamp is curious: per Proud, a regulation of 15 December 1925 stated that all official mail should be superscribed accordingly, but apparently a month later the regulations changed to require a superscription of "official" instead. One imagines the mail room of the Iraq Railways, having commissioned an "on state service" handstamp as required, were in little mood to change it shortly afterwards. Franking is 4½ annas: 3 annas for a foreign letter and 1½ annas for the airmail surcharge.

Some barbarian has gone all over the reverse in biro, as is regrettably evident: I can only assume these are intended to be prices for the stamps as on cover — I have an old money Gibbons which prices these as 4d and 3d respectively (to which then add the 4x on-cover multiplier from the current catalogue).

Baghdad 🠚 Lincoln, 27 October 1928

Another service cover. Here again we have, contrary to regulations, an “on state service” superscription instead of “official”, but a regulation subscription and signature (this time the Public Works Directorate) at the bottom-left. Addressee is Ruston & Hornsby Ltd., an engineering firm which (per Wikipedia) specialised in trains, steam shovels and the like. Like the cover above, franking is a correct 4½ annas.

Baghdad 🠚 Chicago, 2 March 1929

This was definitely a "find", despite its condition: I believe this is, by some margin, the largest Mandate-period franking I've ever come across. Registered envelope from a Mr Murad of Baghdad to Chicago, Illinois, posted on the 2nd March 1929 at the Exchange Square office and arriving in Chicago on the 21st March. Total postage is 4 rupees 10 annas, which is a considerable sum. The cost of a standard-weight registered airmail letter to the USA seems to have been 12 annas at this point (with the usual caveat that I find the treatment of rates in the Proud book somewhat confusing), so clearly we have a very considerable surplus of postage. Which leads naturally to the question of whether this is sincere or a contrivance. I count in its favour the ugliness of it: the sender doesn't seem to have had any aesthetic considerations in mind when placing the stamps (though there's more variety than was probably strictly necessary), and the recipient has opened the envelope roughly, destroying the ½ anna stamp on the reverse. Mr Nielsen, from a quick google, seems to have been an academic in the physics/engineering sort of area and has no obvious philatelic associations. Shortly after winning this cover I lost an auction for one with the same sender and recipient, from the same seller: that one was franked with 1 rupee and change and was entirely conventional-looking.

All of which is dancing somewhat around the question of why the postage is so high: this is actually a relatively small cover, so I think there must be a practical limit on how much it could have weighed with its contents enclosed. I don't think this could've been insured: insurance would be the other obvious way for the franking to increase but, while I've never seen an insured cover from this period, ones from the 1930s have distinctive red markings which this lacks. Conversely, we see that the U.S. customs opened this up on arrival, which presumably they wouldn't have done unless they suspected it to have undeclared valuable contents. The general shape of the envelope plus its robust sealing also indicates that this might have carried something unusual. All very mysterious.

The purple "registered" stamp on the obverse is presumably an American marking, likewise the strange purple smearing on the reverse.

Baghdad 🠚 Beirut, 3 April 1930

Splendid large cover to a Mr Tabet, a senior(?) postal official in Beirut. Posted in Baghdad on 3 April 1930, arrived in Damascus the following day, and there’s an illegible Beirut postmark. Also on the obverse is a genteel old-world “Carlton Hotel, Baghdad” handstamp, and possibly the name of the sender, a Mr Jagger(?). The text in red pencil is of unclear purpose: it adds a “recommandé” which was missing, and then gives the registration and airmail superscriptions in English, rotated ninety degrees.

Total franking is 30 annas: subtract 3 for the registration fee and the letter must have weighed between 101 and 110 grams, as this gives us 10½ annas for postage and 16½ annas airmail surcharge.

Baghdad 🠚 London, 12 May 1932

Registered airmail letter from a Mr Zilkha of Baghdad to Lloyd's Bank, London. Posted at Baghdad's Exchange Square post office on the 12th May 1932, arrived later that day at Baghdad's main office, and reached its destination on the 18th May. Second weight step for an overseas letter (21-40 grams) is 23 fils (15+8) and the third weight step for the airmail surcharge (21-30 grams) is 60 fils (20+20+20), so 83 fils in total plus the standard registration fee of 15 fils gives us the final total of 98.

Of note here is the combination of the first and second 1932 issues: this was posted on Thursday 12th May — that is, the fourth day the second issue was available (it having been issued on Monday 9th). Evidently post offices were authorised to use up whatever stocks of overprinted stamps they still held before moving onto the second issue. We can see here that the Exchange Square office had already run out of overprinted 8 fils stamps (these paid the standard internal letter rate and so were presumably in high demand), but still had some of the overprinted 30 fils stamps left.