FRANCE

GENERAL DUMOURIEZ DEFECTS TO THE AUSTRIANS, 4TH-5TH APRIL 1793

Best, perhaps, to fill in the entire historical background here before getting onto the items themselves. Taken very briefly, in late 1792 Charles François Dumouriez was the commander of the French Armée du Nord, which was at that time grappling with the Austrians in the north-east of France. Dumouriez possessed some genuine skill as a general, and on the 6th November 1792 he won a strong if somewhat disorganised victory over the Austrians at the Battle of Jemappes. This success allowed France to quickly overrun the Austrian Netherlands.

By this point, however, Dumouriez was beginning to grow disillusioned with the revolution of which he had initially been a strong supporter. The radicals in the National Convention were growing in strength, and they began to criticise his conduct of military operations, accusing him of insufficient zeal in fighting the revolution's enemies. Dumouriez argued that after Jemappes his troops were exhausted and over-stretched, and could do no more for the moment. Meanwhile, Louis XVI was put on trial in December and sentenced to death. Dumouriez regarded this as a step too far (seemingly his ideal form of government for France included a constitutional monarch), and he squandered much of the goodwill he had earned after Jemappes by travelling to Paris and fruitlessly attempting to advocate on the King's behalf. Naturally, this made the radicals even more sceptical of his revolutionary bona fides.

Having failed to do much for the King, Dumouriez returned to the theatre of operations. Instead of following up against the Austrians, he elected instead to invade the Dutch Republic — this seems to have been initially done much on his own initiative, although Paris endorsed it after the fact. The campaign against the Dutch became bogged down, and the Austrians took the opportunity to counter-attack, resulting in the defeat of Dumouriez's army at the Battle of Neerwinden on 18th March 1793. The defeat was not in itself a disastrous one, but being beaten caused the easily-spooked revolutionary army to lose its previous enthusiasm, and in the following days a good part of the French army melted away as it retreated. Dumouriez, realising his position was untenable, cut a deal with the Austrian commander, Prince Josias von Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, whereby the French army would evacuate the Austrian Netherlands in exchange for safe passage back to France.

Dumouriez's defeat naturally confirmed everybody's worst suspicions about his competence as a commander, and the fact that he had treated with the Austrians exposed him even further to accusations of crypto-royalism. The Convention duly voted to put him on trial, and demanded he return to Paris to account for himself. Dumouriez realised that all his bridges had been comprehensively burned, and elected to throw his hat in with the Austrians. After much secret negotiating it was agreed that he would march on Paris at the head of his troops, overthrow the republic, and install a constitutional monarchy. In exchange for future concessions the Austrians would stand aside while all this was going on. Paris got wind of what Dumouriez was up to, and dispatched the Minister of War along with four commissioners[1] to arrest him. Dumouriez managed to arrest the Minister and the commissioners, and turned them over to the Austrians: I can't seem to find the exact date this happened but it must have been the 2nd or 3rd April. The coup could now be delayed no longer, but Dumouriez's soldiers were mostly uninterested, and he fled to Austrian territory in disgrace.

Dumouriez never returned to France: he drifted fairly aimlessly around Europe, eventually settling down in England where he died ("to general indifference," says French Wikipedia) in 1823. The Minister and the commissioners were eventually released by the Austrians in a 1795 prisoner exchange.

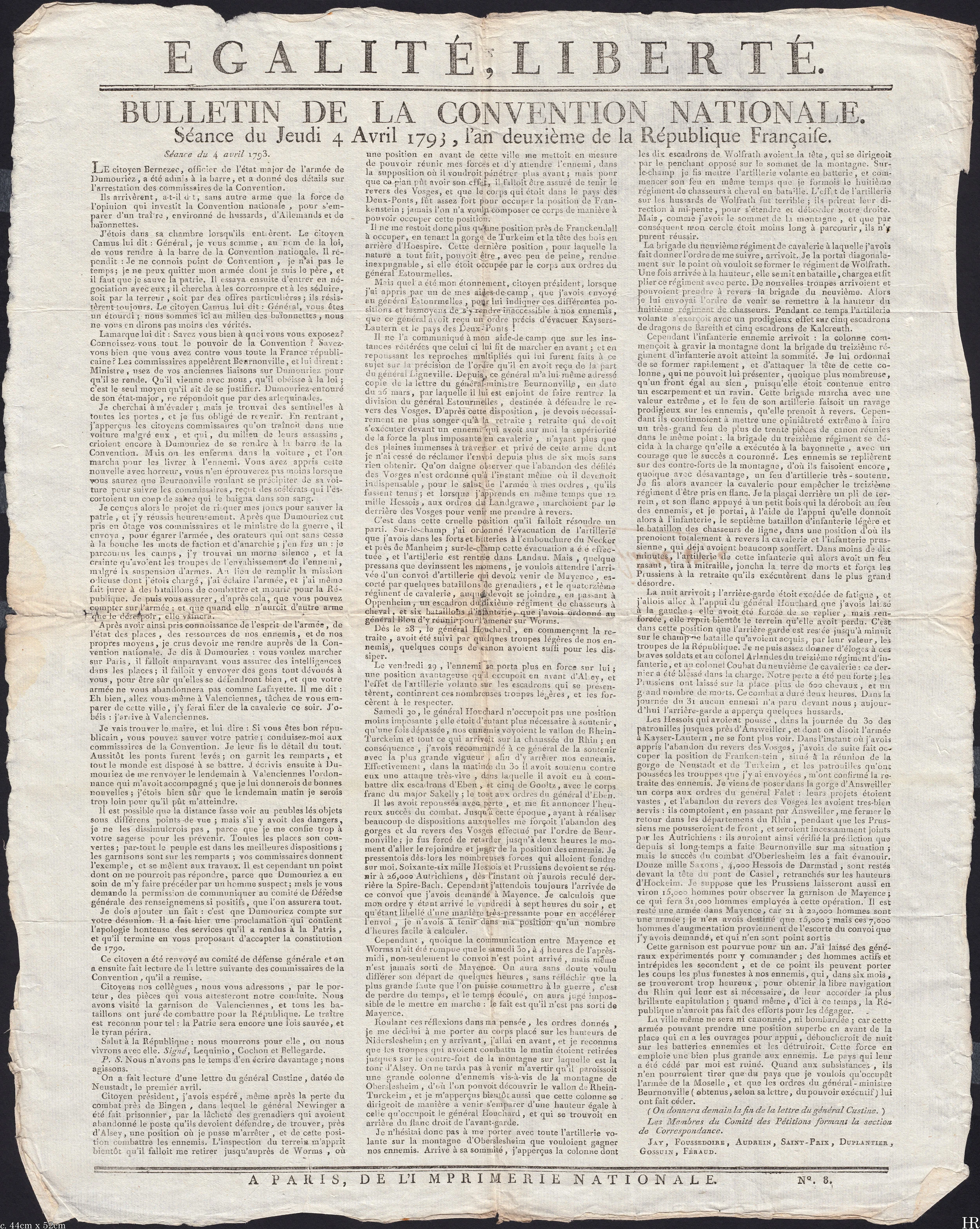

Anyway, the actual documents. First up is the 4th April 1793 instalment of the Bulletin de la Convention Nationale. The Bulletin seems to have been a summary of the debates and discussions of a particular day at the Convention: it's a large, single sheet which I'd imagine was intended to be on public display somewhere. This is in very reasonable condition for its size, I think — the various dog-ears all seem fairly antique so I didn't try to fix any of them, despite the slight visual detriment. We have a considerable amount of text here, and of course I can't read French to any real extent, so I'll just give the following highlights (or what appear to me to be the highlights, from skimming over it), translated very loosely:

1. Citizen Bernezec, an officer in Dumouriez's general staff[2], arrives at the Convention and describes how the the commissioners were arrested. The commissioners, says Bernezec, "carried no weapon but the strength of the Convention's opinion that Dumouriez was a traitor, surrounded by hussars, Germans and bayonets."

- The commissioners demanded Dumouriez return to Paris, but he refused, saying that he was the father of his troops and he could not leave them. He then tried to get the commissioners to come over to his side, "partly by terror, partly by special offers."

- The commissioners could get nowhere, and they asked the Minister to make same demand. Dumouriez's response to the Minister was "like an harlequinade."

- At this point the situation was getting tense and Bernezec tried to escape, only to find that Dumouriez had posted guards at the exits. Dumouriez then had his "assassins" arrest the commissioners and bundle them into a coach. Very gamely, the commissioners were still demanding that Dumouriez surrender himself while this was going on. Dumouriez's soldiers then tried to do the same to the Minister: he resisted and for his trouble he got a sabre blow to the head which "bathed him in his own blood."

- Dumouriez produced some speakers, who tried to get the soldiers on Dumouriez's side (by "pouring unceasing words of factionalism and anarchy out of their mouths"), but the soldiers weren't interested, and remained hateful of the Austrians. Bernezec assures the Convention that the army can still be relied on, and that he even made them swear an oath to die for the Republic.

- Bernezec [feigning loyalty to Dumouriez, seemingly?] told Dumouriez there was a big risk nobody would end up supporting him, as had happened to Lafayette. Dumouriez took this under consideration and ordered Bernezec to go to Valenciennes [at that time in French hands, but a target of the Austrians — they began a siege of it the following month] to persuade its garrison to come over to Dumouriez's side.

- Bernezec, taking the opportunity to escape, duly went to Valenciennes and revealed Dumouriez's plans to the mayor. The mayor, a good republican, put the garrison on high alert against any pro-Dumouriez shenanigans. Bernezec then, very cunningly, wrote reassuringly to Dumouriez, telling him he could expect the loyalty of Valenciennes. He left Valenciennes the following morning and went straight to Paris to warn the Convention.

- Bernezec seems to get circumspect at this point and reminds the Convention that his is just the account of one man: however, it seems clear to him that Dumouriez is up to no good.

- He adds, finally, that Dumouriez is counting on the Convention to be divided and disunited, and claims that Dumouriez issued a proclamation the previous day where he apologised for his services to the Republic, and advocated that the Constitution of 1790 (which provided for a constitutional monarchy) be re-adopted.

2. A letter from three commissioners is read to the Convention: they're in Valenciennes and report that the garrison and defences are in good order. The letter is three sentences long and they apologise for not having had the time to write a longer one.

3. A long letter from General Custine is then read: he reports in detail on recent military operations in the Rhineland.

The next item is a Decree of the Convention, containing two responses to Dumouriez's treachery. First, a declaration that anybody who expresses approval of Dumouriez's coup and his "anti-republican principles" will be punished by death — this is dated the 4th April, the same day as Bernezec's report (which, presumably, was the first time Dumouriez's position was made explicit), so one can imagine it being the spontaneous, instinctive response of an enraged Convention. The next item, dated the 5th, is somewhat more level-headed. It condemns the arrest of the Minister and the commissioners, taking the view that they should have been treated as non-combatants instead of being detained like prisoners of war. The "revolting conduct" of the Austrians in holding the Minister and the commissioners is described as being contrary to all the customs and usages of war, as well as to justice and humanity. So the Convention decides to reciprocate, and announces that certain high-ranking Austrian prisoners-of-war will be held as hostages until the Minister and the commissioners are released. To cause maximum offence, many of the Austrians chosen are relatives of the Prince von Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (and, where appropriate, their voting weight in the Imperial Diet is given). The names are:

- François Xavier, comte Aversperg,

- Auguste, comte de Linange,

- Les deux Labare frères, neveux de Général Clairfait,

- Charles Woldemar, comte régnant de Linange-Westerbourg,

- Ferdinand Charles, son fils, comte héréditaire,

- Frédéric, comte de Linange.

These all seem to have been fairly obscure characters: attempted identifications, where I can make them, are linked. My very limited searches weren't able to track down the Labare brothers or Fréderic de Linange, based on some very crude searching.[3] These guys all seem to have been released in 1795 or thereabouts, at the same time as the Minister and the commissioners were freed.

The Decree also seems to prescribe that anybody else in France with a vote in the Imperial Diet should also be arrested for good measure — with a sensible exception for such persons also currently in service with the French army.

Anyway the Decree itself is a local printing for the Eure département, done at the works of official printer J. J. L. Ancelle in Evreux. As usual, after the set of Paris signatures we have the signatures of the local administrators ceryifying that the text is a true copy of the exemplar decree sent down from Paris.

11 Floréal An. CCXXV

Technical details: scanned at 600dpi (the Bulletin in six parts, each page of the Decree in one part), levelled and resized 50%

[1] Armand-Gaston Camus, Jean Henri Bancal des Issarts, François Lamarque and Nicolas-Marie Quinette.

[2] This Bernezec is a difficult figure to find information on: Google furnishes the Mémorial Revolutionnaire de la Convention, which notes a deputy Bernezec, of the Gard départment, as one of the regicides of Louis XVI.

[3] German Wikipedia, as automatically translated, makes the somewhat gnomic remark that Auguste de Linange "opposed and vehemently supported the revolutionary ideals."