some notes on EQUATORIAL GUINEA UNDER Macías Nguema

Introduction.

On this page I shall try, very tentatively, to sketch out a few notes on this rather macabre corner of African history.

There’s an enormous lacuna in the source material here — really, enormous. The international news media seems to have quit the country in 1969, no doubt out of a reasonable fear for their own safety after the blow-up with Spain. At this point, the historical record (at least for my purposes) more or less entirely and immediately ends. I have seen exactly two photos taken inside the country in the 1970s while Macías was in power, and no footage. Footage of Macías’ rare foreign trips exists but by its nature isn’t extremely helpful. International coverage from inside Equatorial Guinea didn’t resume until August or September 1979, in the aftermath of Macías’ overthrow. Contemporary internal coverage no doubt could be unearthed in Equatoguinean or Spanish archives by intrepid researchers, but is inaccessible to me.

This of course means that none of the 1979 images here are actually from the Macías era. I would imagine, just as a matter of common sense, that any changes to the uniforms would’ve taken longer than a few months to implement — and so I’m assuming that what we see in late 1979, after Macías, is good for the Macías era also.

It will be immediately apparent that the army we see in 1979 looks highly unlike the army we see in 1969, but, lacking almost any evidence for the entire 1970-1978 period, it’s impossible to know when any particular change was introduced.

On top of all this — there just isn’t a lot of material to work with, quantitatively.

Taking all this into account, the descriptions here will thus be extremely tentative, even by my standards.

A note on caps. The contemporary Spanish army employed two styles of soft cap. Both styles can be seen in Equatorial Guinea, and I don’t know the proper names of either. There was a stiff, relatively low cap with fabric peak and fabric chinstrap — I call this the “fatigue cap”. There was also a stiff, relatively higher cap, with a scalloped ear flaps piece in German M43 style fastened by a button on the right-hand side, with a non-functioning button on the opposite left side just for symmetry — I call this the “service cap”.

The army at independence.

At the actual point of independence the army was still Spanish-colonial in ambience. I don’t think I need to say much about this. There’s a very nice overview of the Spanish period, with many excellent photographs, by one Javier de Granda Oride, available here.

The army of 1969.

The purported failed coup and crisis with Spain in 1969 was the first time independent Equatoguinea received any media attention — and, as mentioned in the introduction, the only time until the overthrow of Macías. In the 1969 material the soldiers look like Spanish regulars instead of colonial subjects — no doubt they were excited to discard their fezzes, white shorts, etc., after independence.

Service/field/etc. uniform. Very Spanish in appearance, naturally enough. A rather rich, brownish tan fatigue cap, tunic and trousers, worn with black boots or shoes. A light greyish short-sleeved shirt. The shirt on its own is seen far more commonly than the tunic. Occasionally shorts can be seen, the same colour as the shirt, worn with white socks [fig. 6]. The caps had blue tops [figs. 5, 13] and a blue star badge [figs. 7, 8] (not always present), and the chinstrap buttons I think were brown(?). Rank insignia was worn on the front of the cap, under the badge [fig. 8]. The tunic had gold buttons, and a blue device of some sort (another star?) on the shoulder straps [fig. 9]. Some men can be seen with an illegible upper left sleeve insignia, in blue and white(?) [fig. 10]. I haven’t seen any men with rank insignia on their bodies — by analogy with contemporary Spanish and later Equatoguinean practice, I’d assume this was worn on the shoulder straps of the tunic, or above the left breast pocket on the shirt. One man can be seen with an unidentified circled star badge on his left breast pocket [fig. 11]. Belts seem to have been black leather (buckles unclear). Weaponry was some sort of obsolete Mauser-style rifle, worn with twin three-cell black leather pouches [fig. 3], or the Star Z-45, with a single black(?) leather pouch worn off the shoulder [fig. 11].

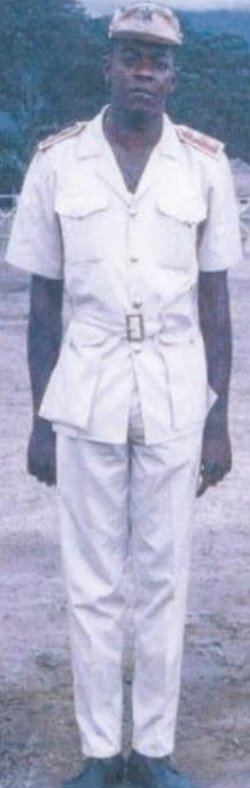

Officers’ service dress. Officers had a distinct service dress: a light tan four-pocket short-sleeved jacket with gold buttons and integral cloth belt (gold open rectangular buckle), straight trousers in the same light tan, and a service or fatigue cap in a darker tan (seemingly still lighter than the brownish tan of the enlisted men), with blue top. This was worn with stiff detachable shoulder straps with gold trim and gold rank insignia, and a gold aiguillette on the right shoulder, sometimes [fig. 13].

Other uniforms. I have very little to say about these. One man has a tan shirt, worn with tan shorts and white socks, and stiff blue shoulder straps — the navy, perhaps? [fig. 14] Another man in black-and-white footage has a light tunic with closed collar and Spanish-style diamond insignia on the collar points, with shoulder straps and white-topped cap. Also navy? [fig. 15] The police seem to have worn a greyish-blue colour, very unclear. [fig. 16]

The army of 1979.

The formal name of the army was originally the Guardia Nacional (by contrast to the former Guardia Colonial), but at some point it seems to have changed to the Ejército Popular Revolucionario.

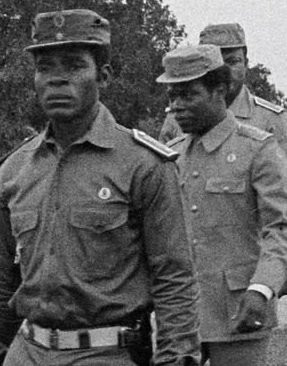

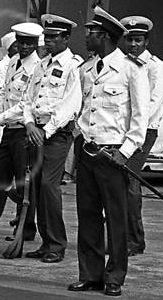

Service/field/etc. uniform. Greyish green fatigues or a slightly neater tan uniform, the latter perhaps held over from the earlier period. Various headgear: service caps, fatigue caps, greyish green peaked caps with fabric chinstraps and peaks [fig. 21 — I don’t think these are police, but I could be wrong], or green Soviet Ssh-60 helmets. The service and fatigue caps lacked the blue tops, and seem to have generally been worn without badges — Teodoro Obiang wore an embroidered version of the army emblem on his service cap (with a gold trim on the peak) [fig. 24] and another officer can be seen with the army emblem, on a disc, on a fatigue cap [fig. 23]. I’ve seen a picture of one of these badges for sale on a militaria website — gold, with “G” and “N” on either side of the army emblem. No doubt many other variations existed. I haven’t seen a good close-up view of a peaked cap. Rank insignia was worn on the front of the cap, below the badge — on the fatigue cap, pinned directly to the chinstrap [figs. 23, 24] . On the fatigues, rank insignia was worn on a red rectangle: at (wearer’s) right, the army emblem, followed by rank markings in a horizontal line [e.g. fig. 20] . This is better attested for officers — how enlisted men managed it I don’t know. Seemingly the rectangles could either be cloth or some stiff material [fig. 23]. The standard firearm seems to have become the SKS, worn with a fabric ammunition belt with suspenders [fig. 18], and AKs, with Soviet-style pouches, are also seen [fig. 26]. The white armbands seen on some men here seem to have been something to do with Macías’ trial, not a standard part of the uniform.

A late 1980 photograph shows men with greenish grey berets (badge unseen) — I haven’t seen these any earlier but I note them for completeness.

Officers’ service dress. The “1969” short-sleeved belted tunic described above [figs. 12, 13] , continued in use. We also see a four-pocket closed-collar tunic [fig. 27], worn with stiff detachable shoulder straps (army emblem above rank insignia), and the fatigues described above, “upgraded” to service dress by the addition of the same stiff detachable shoulder straps [fig. 27]. Colours all unknown but, one assumes greyish green or light tan for the tunics and perhaps a bright colour for the shoulder straps.

There seems also to have been a more formal type of service dress [figs. 29, 30] — I’ve only seen this in footage of Macías’ visits to foreign countries, worn by his aide-de-camp or some such. A tan four-pocket open-collar belted tunic. Gold buttons. Illegible collar insignia. A gold aiguillette off the right shoulder. A tan cap with lighter tan band, gold chinstrap and black peak. Rank insignia worn on the band and what I assume must be the army emblem in metal on the crown. Unusual stiff tan shoulder straps, seemingly with no rank insignia. Straight tan trousers with black shoes.

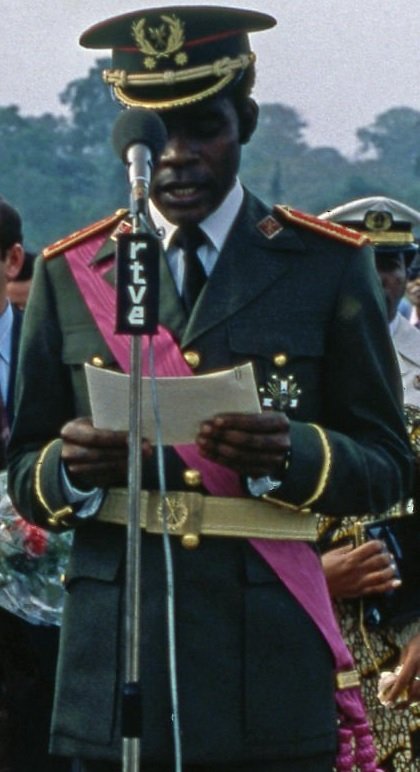

Full dress. Obiang can be seen in this ornate green uniform during the royal visit in December 1979. I wouldn’t be surprised if this was hurriedly got up from a Spanish tailor, rather than something actually worn in the Macías era, but I note it for completeness. Note that the gold edging on the shoulder straps is scalloped rather than straight, as on the ones worn with service dress. The collar insignia seems to be the army emblem, on a background of strong diagonal lines.

Obiang can be seen, in another photograph of the royal visit, wearing a midnight blue double-breasted uniform of vaguely naval style — narrow cold cuff trim and stiff red shoulder boards. The headgear unfortunately unseen.

Other uniforms. A man, presumably of some importance in Obiang’s coup, can be seen wearing an illegible pocket badge, a large cloth aiguillette, and a fatigue cap made from Spanish “amoeba” fabric [fig. 33]. One bit of footage has a single shot of a police officer(?) with green shoulder straps and greyish green cap with gold piping to the crown and both ends of the band, and black chinstrap and peak [fig. 24]. The badge, on the cap crown and shoulder straps, isn’t the army emblem, but I don’t know what it is. A couple of naval uniforms, as seen [figs. 35-36]. A unit, identified as marines, can be seen in some photos of the royal visit — uniforms as pictured [figs. 37-38]. The enlisted men had peakless caps (looking like army caps without peaks, rather than true sailor hats), petty officers and officers peaked caps. Colours unfortunately unclear.

Badges. The couple of actual 1970s Macías era photos I’ve seen show him accompanied by senior officers wearing circular badges, seemingly with Macías’ face on them, above their left pockets [fig. 39]. How widespread this practice was at the time, I unfortunately have no idea. Obiang, very interestingly, can be seen in photographs taken soon after the coup wearing a Spanish colonial-era “Territories of the Gulf of Guinea” badge on his right pocket, with three bars (unidentified) below it [fig. 40]. Subtly indicating his desire for a rapprochement with the former master, no doubt. The star is blue and the letters, edge and bars are gold. Note also the unknown badge worn at fig. 33 above.

9 April 2023